There is more quality information available online to more people than ever before. In 2012, a computer science course, produced by Harvard University broke all records and registered 100,000 students at a sign-up.

Consider this, if an average Harvard Class runs at about $5,000, Harvard has just produced $500M worth of value. Somehow, only 1000 students finished the course and scored their certificate. Immediately, the actualized value went down from half a billion dollars to five million. I am not discounting $5M in any way, but think about this:Why did 99% percent of students give up the class they so eagerly signed up for?

A few things are at play here. First, is the Internet Factor. We have a lurking understanding that things that come from the internet are expected to have a low – engagement and low – commitment rate. We tend to be more flaky with people we met online. We cancel tinder dates last minute or don’t show up at all to view the apartment we found on craigslist.

Think of the email click through rate for Mailchimp campaigns. It’s about 2%. That means that out of a 100 people who signed up for an email list (VOLUNTARILY), only 20 people opened the email, and only two individuals clicked on the link included in the email. Having this in mind, I no longer find it surprising that the drop off rate for online courses is so high.

The second reason for a high drop out rate is the Lack of Peer Pressure. When learning gets hard, and if you are taking a meaningful course it will get hard, what keeps us going is the social pressure from the teacher and classmates. In turn, they might be getting through the course because YOU provide social pressure for them. That clearly works in a regular classroom environment, where a drop off rate is minimal. A lot of authorities and thought leaders in education like Seth Godin as well as ordinary online students, like Pruthveedhar Reddy, whose LinkedIn article I stumbled on in March, begin to realize that fellow students keep us going when going gets tough. What drives us is the innate need to fit in and keep up with the Joneses.

Seth Godin says: when your peers can’t see you, it’s getting hard to see yourself.

Your peers can’t see you, which makes it difficult to see for yourself.

Below, is an excerpt from the LinkedIn article I mentioned above.

In the end, learning from video courses is not as easy as we thought.

Let’s Compare Reading a Book and Watching a Movie.

Have you ever been distracted by someone in a movie theater? Let’s say they start speaking on the phone, texting or having a side converSAT® ion right next to your seat. Do you find that distracting? Even though distractions and noises is an integral part of a collective human experience, a lot of moviegoers find it overly irritating. Anil Dash, a famous witty blogger, wrote a controversial piece about it. I will give you the link later.

Dash’s essay made me reflect on the difference between reading a novel and watching a film. I began to wonder why books—which usually require more concentration to consume than a film—don’t have strict rules like “please silence your cell phones.” In other words: why are we perfectly willing and able to read books on a crowded subway train (find proof on IG: hotdudesreading) or on a park bench in a busy metropolis?

Can anybody really say that being surrounded by screaming baristas in a coffee shop lessens their enjoyment of a novel? I might just be strange, but I actually find that I consume literature far more efficiently when I’m reading in a public place than I do at home. The curious facts remain: we can read in environments that would be considered completely inhospitable for movie-watching. Why?

The easy answer is that movie-watching engages all of the actual senses and only a portion of the imagination. It’s an almost totally PASSIVE act of media consumption. Reading, on the other hand, engages the brain and forces our minds to paint vivid pictures for us. Yes, we are required to build structure and make sense out of the plot which forces our imaginations to work in a very active way.

Back to Educational Videos…

Let’s compare movies and educational videos. Movies usually have richer visuals. Viewers are mesmerized by vivid colors and scenes on the screen. Most educational videos are built in a talking head format. The instructor is speaking to you at a normal pace, about 200 words per minute.

What if I told you that our brain can process 4000 words per minute. That leaves us with 3800 words of mental bandwidth. We can use that cognitive capacity to take notes, connect new concepts to the old concepts or start daydreaming.

Raise your hand if you ever found yourself going through your laundry list while watching an online training video.WATCH THIS and never feel guilty again!

Speaking of building structure…

Our ability to remember things depends on the quality of the initial input and how well we can create order out of what we perceived. How adept we are in navigating the material, leaving out the irrelevant stuff and binding all the important things into a tightly-bound network. When we read, creating order is easier than when watching a video.

Headings, when done well, can be the best reading cues. Good headings help your learning by:

signaling what’s important;

showing you how the text is organized;

demonstrating the value of concepts by the font size of headings and subheadings;

helping you produce better summaries and outlines.

When we are watching a video, information is coming at us at a constant rate. Instructor doesn’t usually stop and explain whether we are moving from an important idea ($100 idea) to a less important concept ($50 idea or a $5 idea.)

Major Advantage of Text over Video.

I often say that the best thing I have done as an online learner was to create my own video course. I was able to see with my own eye what process online instructors go through to create a course. When instructors build a video course, they must think about their audience first. In particular, they need to know how much background knowledge their audience possesses. Since not too many instructors are professional clairvoyants, they can’t predict what their future students from all over the world do and don’t know. To be safe and not to exclude anyone. a lot of online teachers assume that the amount of knowledge their students possess is minimal.

How does that impact the curriculum? Every semi-unfamiliar term will be explained and clarified. That means that the course will be most likely be created for beginners and the teacher will pace his students at a minimal speed.

That works really well for the rookies, but what about those who happen to be advanced? Let me give you a personal example with a course on machine learning.

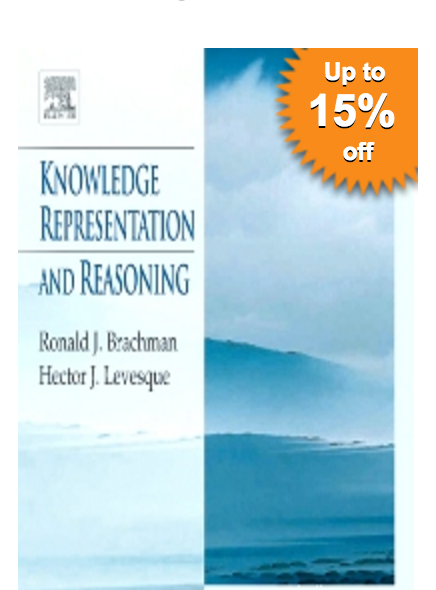

A few years ago, this book appeared on my to-do list

One of my clients was reading it and I agreed to be his accountability buddy. What that means is that I had to read the book with him and quiz him on different chapters. As a result of that unplanned learning, I now know what reasoning and KR (Knowledge Representation) is. I also know a lot about AI and Machine Learning. However, I don’t consider myself advanced in any way, I had a bit of background, not more than that.

In March 2016 someone forwarded me an article about Katyusha, the First Direct Acceleration of Stochastic Gradient Methods. The reason this article was forwarded was not because I find stochastic gradients sexy, but because Katyusha is another popular version of my name. My mom uses this version (Katyusha) when she is pleased with me. Otherwise, it’s just Katya.

As I opened the article, I realized I didn’t understand a word of it and as a good reader, I started looking for some background information. I went straight to YouTube. My instinct told me to search: “Machine learning.” I found a course from Stanford. I figured if I watch one or two lectures, I will gain some knowledge necessary to read the article and speak intelligently about Katyusha gradient methods and machine learning overall.

I found myself at minute 36 not learning a single thing. I didn’t feel like speeding up or scrolling because it’s Stanford after all. It’s like baking cookies and not eating them, its obligatory. I didn’t feel like blaming the instructor at all; I knew what he was doing. He was laying the foundation for everyone. The dude is a co-founder of Coursera for Heaven’s sake; he does know a thing or two about class instruction. Perhaps, it was a great speed for some students, but not for me. I decided to take control of my learning. I opened a wiki page on Machine Learning, breezed through what I already knew and started filling up some significant gaps in my knowledge.

That felt like a more productive way to learn. I felt in control this time.

I often do this with articles, especially with the lengthy kind. My lengthy favorite blogger is Tim Urban. I highly recommend him if you are into some long reads. Let me use his Elon Musk series as an example. His articles begin with a short bio of Elon 3-4 paragraphs long. I deliberately skip it, because I read a whole book by Ashlee Vance on Elon’s life. I feel empowered to skip certain paragraphs because I value my time and don’t want to get bored. Skipping around in text is easy because you can look ahead. If Tim were doing a video, it would have been much harder to navigate, leave out what you already know and move to the complexound pieces.

We don’t finish anything.

Okay, this is not exactly video specific but true. It’s true about learning as a whole. We don’t finish reading 85% of articles; I am really surprised you are still going. Even my mom stopped reading by now. As I was researching this topic I wanted to have most accurate data possible and decided to get it directly from the source – learning platforms themselves. Most executives liked the idea of my research, and only a few gave me access to charts and stats that would reflect viewer’s behavior. Those resources were shared confidentially, of course.

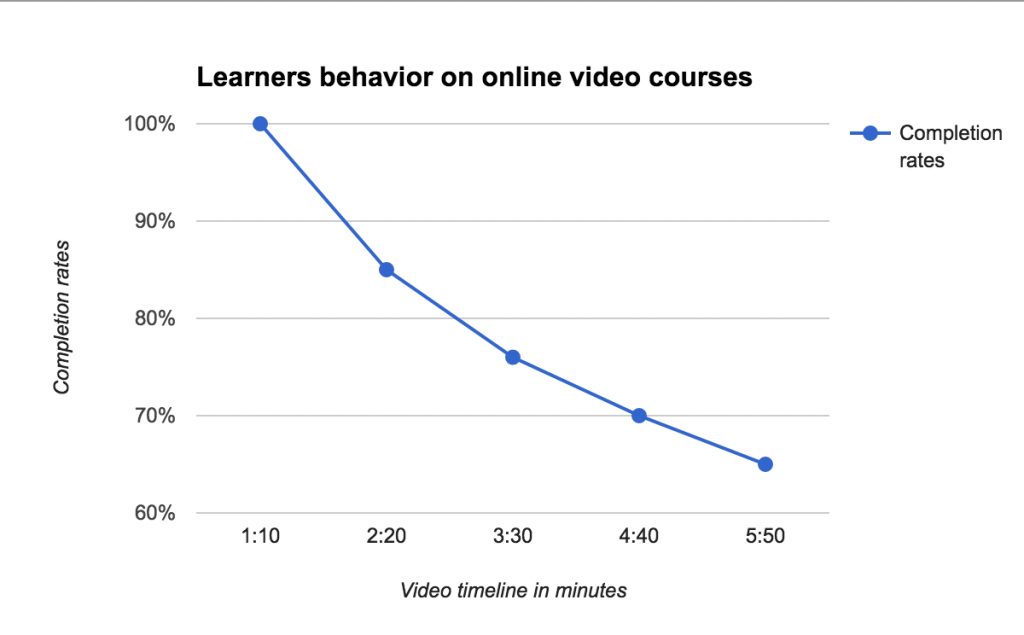

Below is a graph that represents completion rates for Lesson 1 across ten different courses. Lesson 1 tends to get most views; that’s why I picked it for my analysis

Out of the 100 people who start watching Lesson 1, on an average, only 63% finish it. This drops further as the duration of the video increases. An optimal duration of the video is about 8 minutes.

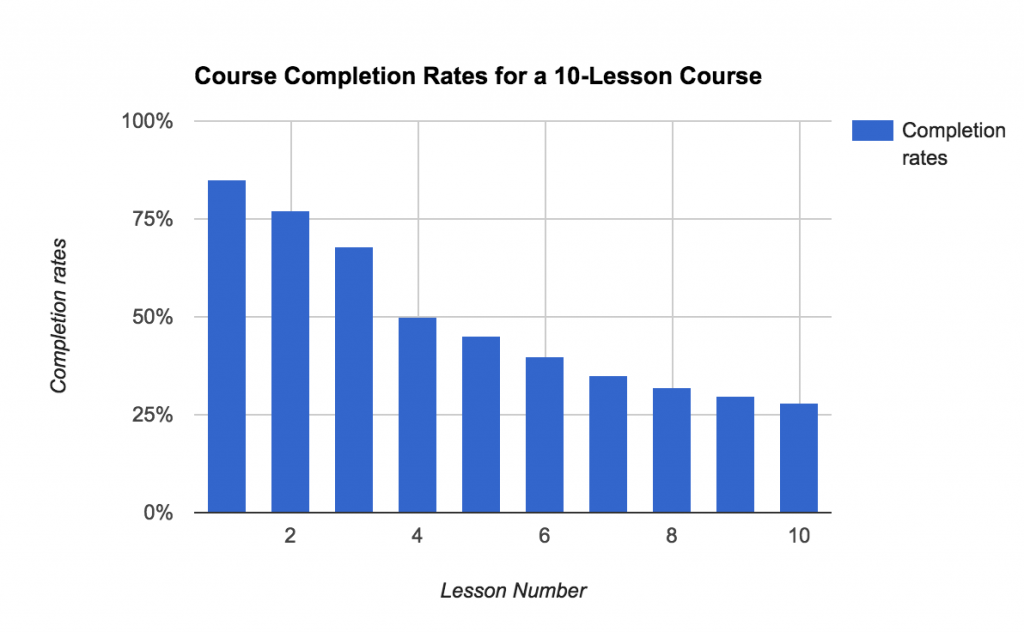

We don’t just not finish watching a single video; we don’t complete whole courses. Below is a graph that represents completion rates of 10 – lesson courses.

Autoplay feature can play a big role in why we don’t finish watching videos. While we can benefit from videos playing constantly making us move forward with the material, we are no longer in charge of learning. We don’t get to decide whether you have enough time, focus or mental bandwidth left to take in new information. The decision is made for us. Click next, is a familiar, cozy feature taken right from Netflix.

Conclusion

I hope that brought into light some of the common problems we face while learning from online courses. Were you able to relate to them? Are there any other problems that you faced and could be added to this list? Please let me know. I am also working on the other side – the solutions to these problems. By engaging with industry leaders, and executives from learning firms, as well as online learners, I am working towards a solution to these problems, and any inputs in this regard would be most welcome. Thanks for stopping by.