One of the reasons online courses are so popular is because learners surmise that the brain can be magically hooked up to a computer in order to download information onto their cortex at a fast and efficient rate. I am often asked about listening to courses at double speed or faster.

“Will I be able to understand/process/remember what I hear if I go X2 or X3 the speed?”

I realize that reading and learning is becoming more and more transactional in the current world. It’s hard for me to imagine some of my clients curling up with a 600 pager on the couch for hours on end or spending 4 hours on the weekend watching one of the masterpieces from the great courses. Instead, my clients are speeding through a book in a couple of hours, extracting most valuable information from a recorded lecture by replaying it at X2 speed and selective listening to a podcast at faster rates.

The idea of listening at double speed is not new or revolutionary. Apple introduced variable playback speeds into its iPod software back in 2004. Along with many productivity experts, David Allen in the “Getting Things Done” blog recommended “adjusting the playback speed of your audiobook or video to a maximum of 150 percent” to complete the book more quickly.

To answer the question whether it actually works, let’s take a look at processing speeds that our brain is capable of.

When we compare the capacity of our brain to the computer terms, it is minuscule indeed. Scientists give a range from 110 to 100 bits per second. When one person is talking at a regular speed, they communicate information at about 60 bits per second. For that very reason, most people have a hard time hearing two people speak at the same time. That happens because the sum of the two inputs (60 bits +60 bits = 120 bits) is higher than our upper limit for processing (110 bits).

Individual’s ability to analyze and make sense of information taken in through the ears is profoundly impacted by the person’s auditory sequential capacity. At ExecutiveMind, we measure auditory sequential processing when we assess a new client. We also assess it after we finished our cognitive training work to monitor changes and improvements. If the sensory processing number is initially high (8, 9 or more) we find that people can easily listen and internalize information they heard at X2 or X2.5 speed. When the number is low, clients have a harder time tuning into faster speeds. This is different from problems involving hearing, such as deafness or being hard of hearing. Difficulties with auditory processing do not affect what is heard by the ear, but do affect how this information is interpreted and processed by the brain.

Some learners are annoyed by the chipmunk voices (the usual side effect of going at X2.5 speed or faster) or seeing videos in highly animated modes.

I’d like to warn you in advance and say that there is really no universal prescription or recommendation of speed here. It not only varies from person to person, from author to author, but also from medium to medium.

We find that speeding up a video course is easier that speeding up an audiobook. Here is why.

Usually, a video course will have an audio track synced with a “talking head” video. If you crank up the replay speed to X2 or higher, you can still get some additional visual cues of what the teacher is saying by reading the instructor’s lips or the slides. When it comes to audiobooks, you don’t get to see the author or the narrator reading the book. Information solely goes into your brain through your ears leaving your eyes to wander around and possibly find opportunities for distractions. Recommendation: If you are serious about learning from the audiobook, rather than just being entertained, you can achieve it by occupying your eyes with the related visual task. Here is what we mean by that. Find a non-destructive place for you, take out a blank sheet of paper and begin taking notes about the concepts you are learning. Also, make sure you are sitting at a table, rather than walking around, cleaning your house or driving.

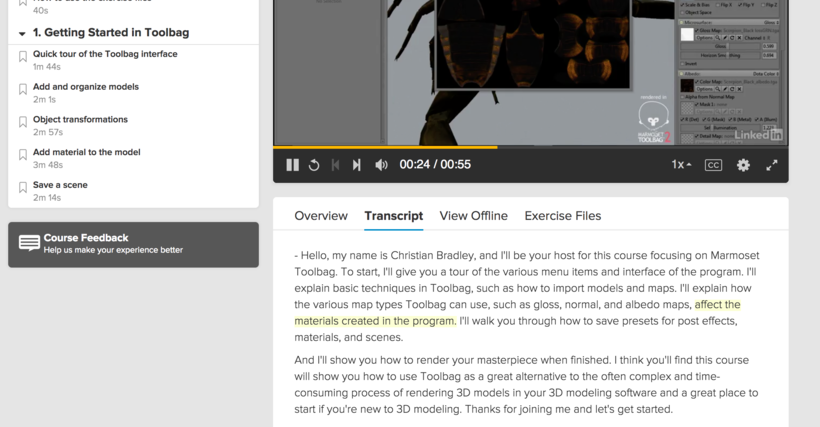

Also, keep in mind that video lessons are usually done as free speech (except than Lynda.com and a few others) when an instructor explains a concept or idea in their own words. “Free flowing speech” of video instructors creates some sound gaps and ultimately makes room for compression. In the meantime, audiobooks are heavily edited and well thought through. A book author has crafted an exciting, fast-paced narrative; painstakingly chose words, deliberated over the lengths and tones and rhythms of sentences and probably eliminated the sound gaps already.

Video lessons have another bonus. A lot of learning platforms like Lynda, Ted, Coursera have interactive transcripts. That allows you to hear and read the scripts of the lecture at the same time; some experts call it multisensory learning. That keeps your ears and eyes on the content. If your processing capacity is high, you should feel confident cranking up your speed to X2 or even X3 and follow the interactive transcript along with listening to the sped up lecture.

The use of interactive transcript opens the “door” to smart listening and smart learning. Specifically, the ability to go faster or slower in specific parts of the lecture! Many platforms have the transcript search feature, the ability to search for a keyword and jump to that specific point, not only in the lecture but throughout the course videos.

As a foreigner, I can certainly appreciate having access to a transcript. If it’s hard to for you to understand English as a second language, you should try looking at transcripts alongside listening. Whether understanding the new class terminology or learning English as a second language, multi-sensory learning is preferred. By simultaneously reading and listening to information, several learning centers are stimulated, improving recall.

Contrary to the common belief, when we read at a faster rate, we tend to focus more. The same thing happens when we listen to someone speaks fast. We try to use all of our mental bandwidths to keep up, which prevents distractions from occurring.

I encourage you to try speed listening if you haven’t already. Make sure you are not going too fast and sacrificing speed for learning because mere watching the lecture or finishing the audiobook does NOT equal learning.

The article is written by Katya Seberson, a memory and learning expert, founder of ExecutiveMind and an online instructor on Udemy.